The Development of Evangelicalism and Rise of Fundamentalism

This is part 2 of a four-part series on Christianity in the USA: Evangelical Christianity was invented in the 18th century and became Fundamentalist by the 20th.

Part 1: Persecution and Escape: Christianity in Colonial North America

Part 2 (this post): The Development of Evangelicalism and Rise of Fundamentalism

In the early eighteenth century, various officially established religions existed among the thirteen English colonies in North America. Religion was otherwise diverse within the general scope of Protestantism. Church membership was low, having failed to keep up with population growth. Public worship tended to be formalistic, routinized, and largely devoid of experiential expressions of faith. Some ministers—influenced by the vestigial Puritan emphasis on an individual, personal conversion experience, the Presbyterian emphasis on doctrinal precision, and the Pietist emphasis on individual devotion and personal religious fervor—began calling for a revival of religion and piety.

These influences were combined to produce an evangelical form of Protestantism that placed great importance on seasons of revival, characterized by outpourings of the Holy Spirit, as evidenced by the emotional responses of sinners having individual, personal conversion experiences. During the 1710s and 1720s, such revivals became frequent among New England Congregationalists, with much of the energy coming from young converts. By the 1720s and 1730s, an evangelical party that promoted such revivals began to take shape within the Presbyterian Church in the Middle Colonies. Tensions between proponents and opponents of this new cross-denominational movement would lead to the Congregational and Presbyterian churches splitting, while strengthening the Baptist and emerging Methodist denominations.

In the fall of 1734, the Congregational minister Jonathan Edwards, mentioned in the previous post, preached a series of sermons to his congregation in Northampton, Massachusetts, on justification by faith alone (see my post, Luther’s Personal Issues and the Protestant Concept of Salvation). The most famous of Edwards’ sermons was entitled “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.” This classic hellfire sermon was highly influential in the context of the Great Awakening and provides insight into the movement’s theology.

Using vivid imagery, relevant observations, and selected scriptures, Edwards presents an enraged God of ever-thinning patience and restraint who is wrathful toward unbelievers, consigning them to well-deserved destruction in a very real, horrific, and fiery hell after their death, which may come at any moment according to God’s will (see my post, Is Hell Real, Or About Vivid Imagination and Bad Translation?). Those who follow Christ’s urgent call to receive forgiveness and salvation through belief and trust in Christ may receive the comforting hope of salvation, replacing their fear of eternal damnation (see my post, Eternal Damnation Was Invented 400 Years After Jesus).

I wrote this in a previous post:

Maintaining this interpretation requires assuming the dysfunctional theology of an exacting and cruel God whose grace is somehow delimited by the need to punish. This cannot be considered grace in any sense. While some passages [in the Hebrew Bible] depict a wrathful YHVH, and while there certainly are fathers who behave in this way toward their children, such a theology hardly reflects Jesus’ words and teachings about God as a loving Father (see Jesus Dying in Your Place Was Invented 1000 Years After Jesus).

Most of the basic elements of what we know today as conservative, Protestant, fundamentalist, and evangelical Christianity in the USA and beyond can be found in the novel combination of elements that characterize the religion of the Great Awakening.

Sin as the defining problem of human existence

A God inherently displeased with sinful humanity

A sinful humanity inherently displeasing to God

Factual, supernatural, eternal hell

Emotional fervor

Individual, personal conversion experience through faith in and surrender to Christ

Inward assurance of salvation thereafter

Correctness of belief

It should be noted that a Christianity combining these elements did not exist in this form before the revival movement that brought them together. The scriptural basis for such a combination of elements requires the selection of passages removed from their contexts and assembled as a retrofit. If one were to develop an expository outline of this form of Christianity and place it next to a list summarizing the basic gospel teachings of Jesus and the essence of the apostles’ instructions to the early church, one would find two different things.

Check out the ARCHIVE of Faith Shifter posts.

Also notable is that this scheme for Christianity brings forward the modern ethos of precisely defined doctrine, coupled with guilt and emotional response to it, and the defining of an exact moment for personal salvation. This stands over and against the ancient practice of an ongoing silent journey inward, a self-emptying kenosis, and giving one’s heart to Jesus and his example of oneness with the Divine.

Evangelicalism split the most common forms of Protestantism into two different groups. Non-evangelicals (who would become known as ‘mainline’ Protestants) continued with more liturgically-oriented forms of worship and process-lifecycle approaches to ritual. Evangelicals shifted to more extemporaneous approaches, the seeming spontaneity of which was considered evidence of the Holy Spirit. While engaging the same orders of worship, behaviors, and manners of prayer, again and again, constitutes a de facto unwritten liturgy, acknowledging as much would remove the evidence of the Spirit supposedly found in such ‘spontaneity’.

The influence of religion from the Great Awaking on the synthesis and shaping of a quintessentially U.S. American form of Christianity can hardly be overstated. Far beyond its initial effect of producing converts and increasing church membership and revenue in New England and the Middle Colonies, this new form of Christianity would cycle through several multi-decade revival movements, reflecting and informing to a considerable degree the underpinnings of American society for better or worse in conjunction with the ongoing development of white supremacy, westward expansion of the USA, development of geopolitical power, and promotion of American authoritarianism down to the present day.

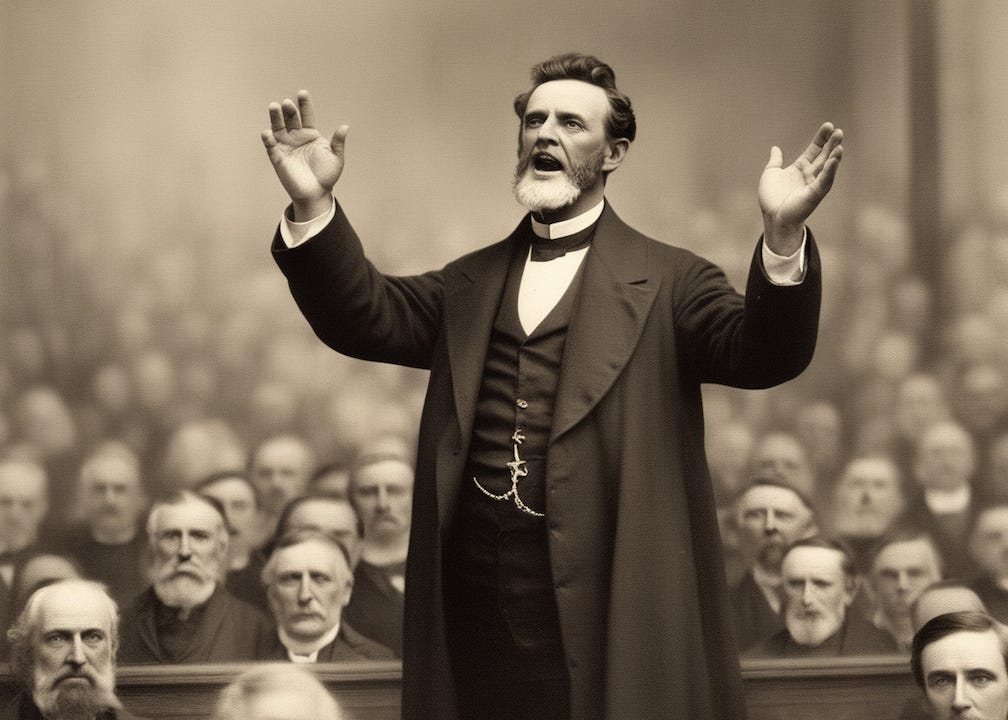

Some refer to the revival movement of ca. 1730–55 as the First Great Awakening, with a subsequent Second, Third, and even Fourth within the scope of U.S. history. There have been multiple waves of revivalism according to the same formula and set of beliefs, each with unique characteristics, additions, and innovations. All of them involved mass meetings, passionate preaching, enthusiasm and emotion, an appeal to the supernatural, and an attendant upsurge in the establishment and growth of evangelical churches.

During the first decades of the nineteenth century, a revival involving several denominations swept across newly settled territories in Kentucky, Indiana, Tennessee, and southern Ohio. Methodist circuit-riding preachers and Baptist ministers worked to evangelize the populace. Camp meetings were a popular vehicle for this movement. Church establishment and membership soared. The majority of converts were women. One theological feature of this wave was Postmillennialism. Christians had a duty to purify society and institute a period of peace and happiness, after which Christ would return. This ultimately became part of the wider impetus toward social reform and progress in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Another wave of revivalism occurred during the latter half of the nineteenth century. Notables included evangelist Dwight L. Moody, gospel singer Ira Sankey, William Booth (founder of the Salvation Army), and English evangelist Charles Spurgeon, among others. This movement was associated with Abolitionism, the temperance movement, and the establishment of missionary societies to evangelize the world.

Fundamentalism

But, something happened along the way that diverted the focus of emerging evangelical Christianity away from progressivism and social reform. That something was the movement within it that became known as Fundamentalism. It was initially a reaction against theological modernism, which sought to revise traditional Christian beliefs to accommodate new developments in the natural and social sciences, especially the biological theory of evolution, and to apply historical and critical approaches to biblical hermeneutics. Traditionalists saw this as a threat to Christianity. They favored an exclusively literal reading of creation, genealogical, historical, and miraculous narratives of the Bible.

The term ‘Fundamentalism’ comes from the ‘five fundamentals’ espoused from within the movement, namely, biblical inerrancy (that is, its factuality), the divinity of Jesus, his (literal) virgin birth, his (literal) resurrection, and his immanent and bodily return to Earth.[1] One can immediately see the application of empirical factuality to biblical narratives (see Is Religious Belief About Facts Outside Us, Or Realities Within?), along with a lack of awareness that a human reader’s limitations shape the interpretation of a text (see Scripture Is One Thing – Your Interpretation of It Is Another). Princeton Seminary professor Charles Hodge interpreted “inspired” from Second Timothy 3:16 to mean that God “breathed” his exact thoughts into the biblical writers, which essentially describes a form of magical dictation. Princeton theologians held that Christian modernism and liberalism were tantamount to a rejection of the beliefs necessary for salvation (as they saw them), and therefore sent people to a literal hell, the same as any non-Christian religion.

The progressivist notion that human societies can be improved, and the human condition advanced over time not only became associated with the modernist thinking rejected by Fundamentalists, but it was also seen as a threat to the idea that the sole problem of the human condition is individual sin, which is irredeemable apart from individual Christian conversion experience. Thus, many evangelicals ultimately rejected the ‘social gospel’ that developed out of the Great Awakening and its subsequent cycles in favor of individual sin as the core problem of—and individual personal religious conversion as the only solution to—the human condition.

The twentieth century also saw the rise of charismatic forms of religion within evangelical Christianity. The Pentecostal and other such denominations were established, charismatic movements took place within already established denominations, and non-denominational churches were established. Charismatic Christianity emphasizes spiritual gifts and the work of the Holy Spirit evidenced by glossolalia (speaking in tongues), extemporaneous prophecy, ecstatic swooning, and miraculous healing. Some groups consider glossolalia essential to being ‘filled with the Holy Spirit’, while others do not.

The development and spread of evangelical Christianity did not affect all of Christianity in the USA. Mainline Protestantism, Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and other forms of Christianity brought by waves of immigration, and the establishment of new sects with unique teachings and practices, all continued unabated through these developments. Evangelical Christianity in the USA would eventually adopt a set of newly invented teachings about ‘the end times’ known as dispensational eschatology. Evangelicals outside the USA would largely reject its novel doctrines. Next week’s post is about that uniquely American Christian phenomenon.

[1] Lower-case f ‘fundamentalism’ has since come to refer to any form of religion or ideology that upholds belief in the strict and literal interpretation of its texts, places it at the authoritative center of society or state, and is socially or politically reactionary.